THE THYROID, T3 and REVERSE T3 DOMINANCE

The thyroid gland secretes 2 tyrosine-based hormones: triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4).

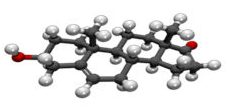

T4, a protein molecule with 4 Iodine atoms, is an inactive “prohormone”. It is the raw material from which T3 is produced by enzymatic “deiodinisation” (removal of one, particular Iodine atom). T3 has a particular shape which allows it to fit into its receptor and turn it on.

All of the biological activity of thyroid hormones is due to T3: it “plugs in” to the T3 receptors which are present in every cell in the body and activates them.

No receptors have been identified for T4. Thus T3 is the body’s “accelerator” (no, not its “Cocaine”): it increases the metabolic efficiency of all cells, thus regulating body temperature, heart and skeletal muscle efficiency, body weight, glucose/cholesterol management and everything else from hair and fingernail growth to thinking power.

Thus it controls every cell in the body and brain, promoting optimal growth, development, function and maintenance of all body tissues, including nerve, skeletal and reproductive tissue.*

It is, particularly, essential for brain development.**

In a healthy human the thyroid secretes all the T4 (about 90 to 100mcg daily) and 20% of the T3. The thyroid does not produce a T3 supply for all cells. Every cell throughout the body, except the Pituitary gland, has a supply of “5-deiodinase” (type 2 & type 3) and each uses type 2 to turn T4 into T3 for itself, applying the T3 to maximise its efficiency.

Under stress conditions however, probably in response to Cortisol release from the stress, the cells employ Type 3, instead of Type 2, 5-deiodinase: Type 3 removes a different Iodine atom, producing a “twisted” form of T3 called “reverse T3” (rT3): rT3 is chemically the same as T3, but the three-dimensional arrangement of its atoms is different and therefore it is nonfunctional.

rT3 does not keep T3 out of the receptors, as previously suggested, but Type 3 deiodinase doesn’t only destroy T4: it also degrades T3 in the blood by removing a second Iodine atom, producing T2, which is also nonfunctional.

So under stress there is a drastic reduction of available T3 inside the cells.

This is why it’s important to check rT3 levels: a high reverse T3 tells us that (1) T4 metabolism has been “skewed” towards reduced T3 production,

(2) Increased conversion of T3 to (inactive) T2 is “happening” and

(3) Entry of T4 into the cells has been reduced.

In other words an elevation of rT3, which can be confirmed by calculation of the T3/rT3 ratio, is a “marker” (a blood test signal) for stress-related metabolic hypothyroidism, regardless of the TSH and T4 levels, which may be normal.

FUNCTIONAL HYPOTHYROIDISM

Stress-related T3 deficiency, previously called “Reverse T3 dominance”, is called “Functional Hypothyroidism” by the Metabolic Medicine community.

It is characterised by reduction of serum T3 from the individual’s usual level, down to the low end of the “normal” T3 range, accompanied by an elevated reverse T3 (please read the notes on “NORMAL”).

The principal clue to the diagnosis is an increase of the T3/rT3 ratio to more than 20.00, along with development of hypothyroid symptoms.

CALCULATING THYROID TEST RESULTS (see the “T3/rT3 ratio” table, below):

In the bloodstream, a serum protein captures a lot of the T3, holding it as a backup supply and that portion of the total T3 is inactive, so WE DON’T CHECK TOTAL T3: we check the “FREE”, UNBOUND T3: references to “T3” in this webpage always mean “Free T3” (FT3).

Calculating the FT3/rT3 ratio is simple in principle, but mystifying for those who aren’t mathematically inclined: you need to convert the FT3 value from Picomoles/Litre, to Nanograms/DeciLitre, so as use the scale in which rT3 is reported.

TO DO SO: divide the FT3 value by 0.0154 (eg, 4.0 Pm/L /0.0154 = 259.74 Ng/DL).

Then divide the FT3 (Ng/DL) value by the rT3 value: if rT3 is 15, 259.74/15 yields the product: 17.3.

NOTE that a ratio of > 20 is normal, >24 is excellent (my opinion) and < 20 indicates low thyroid balance, which is easily and safely treated with a slow-release formulation of Triiodothyronine (NOT rapid-release “Cytomel”).

To make it quick and easy, see the “worksheet” I used when I was in practice, below (this is an internal link, which will not work in your browser): with this reference chart, all you need is the number at the intersection of the (horizontal) T3 row and the (vertical) rT3 column.

THE FT3/ rT3 TABLE: open with excel or compatible app.

Column 1 shows Ft3 in Pm/L.

Column 2 is FT3 in Ng/DL.

First row shows rT3.

The FT3/rT3 ratio appears at the row/column intersections:

PINK AREA = normal, WHITE AREA = Functional Hypothyroid range….

TREATMENT OF FUNCTIONAL HYPOTHYROIDISM:

Functional Hypothyroidism is easily treated with slow-release T3, but most doctors do not believe in, accept or even recognise the diagnosis.

They call it “low T3 syndrome” and prescribe T4. This is disastrous, because the T4 is preferentially metabolised to rT3: that explains why many Hypothyroid patients get worse when they take T4.

HOW MUCH T3 does the person need?

Everyone has an individual requirement for T3, so we begin with the lowest possible amount and increase it sequentially, using blood tests to determine when the correct dose has been reached.

Most people’s “blood – brain barrier” allows T3 to enter the brain and the pituitary easily.

As T3 comes in, the pituitary reduces TSH production: the thyroid responds by making less T4, so on-treatment tests show T3 up, TSH very low, T4 also low.

However sometimes the BBB blocks T3 and in those cases the TSH goes up, but the thyroid, it seems, is also sensitive to T3 level. In these people, the thyroid doesn’t get its usual “kick” from the TSH, so tests show T3 and TSH up, T4 at mid-range. This is easily corrected by adding some T4 to the Rx or by switching to desiccated thyroid, which has 70% T3 and 30% T4.

REMISSION:

Spontaneous remission of functional hypothyroidism may follow stress relief, because preferential use of Deiodinase #3 stops when the stress level and Cortisol output return to normal. However most subjects promptly increase rT3 production and relapse into functional hypothyroidism when a stressful situation arises (best example, Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy).

“ADRENAL FATIGUE”

Stress causes the adrenal glands to increase cortisol output as a short-term response.

Cortisol inhibits type 2, 5-deiodinase enzyme, reducing conversion of T4 into T3 and it also triggers Type 3 deiodinase, reducing T3 production from T4 and increasing conversion of T3 into (inactive) T2: by these mechanisms, it acts to heighten functional hypothyroidism (FH).

After a while, with continued stress-related FH, the adrenals no longer respond with high cortisol production: practitioners who are unfamiliar with deiodinase metabolism, at a loss to explain the continuing complaints, have assumed that the symptoms are due to low cortisol production and have labelled the condition “Adrenal Fatigue”.

Therefore many ill effects caused by Functional Hypothyroidsm are blamed on “Adrenal Fatigue”, which fanciful label is to my mind, inappropriate .

*Low T3 (hypothyroidism) in young women can cause infertility or abortion.

** If a pregnancy persists, T3 deficiency during the first trimester may cause maldevelopment of the baby’s central nervous system, causing (variable) learning disability, ADD/ADHD, Autism and/or Schizophrenia.

The foetus begins T4-to-T3 conversion for itself at approximately 12 weeks gestation and thereafter, is independent of the mother’s T4 supply, as long as sufficient iodine and selenium are available in the mother’s blood.

*** Stress may be physical or psychological:

“Perceived stress” is stress which is subconsciously perceived by the brain, even if the individual claims to be stress-free.

Causes of “perceived stress” which reduces T3 production include: “modern life”, psychoshock (including abuse), inflammation, dieting, nutrient deficiencies such as low iron, selenium, zinc, chromium or iodine, low vitamins B6, B12 or D, diabetes, pain, environmental toxins, free radical load, hemorrhage, acute systemic illness, life-threatening infections, injury, surgery, metal overload, PTSD and hormone deficiencies, heart failure or other chronic diseases.

Perceived stress, with or without subjective or objective stress, is present in close to 100% of ICU patients and can be proved by checking the rT3 test. “Subjective stress” is consciously noted, “felt” and can be described, by the individual.

“Objective stress” is stress to, or on, the individual, as observed by others.

**** ”Functional hypothyroidism” is a condition in which “T3”, the active thyroid hormone, stops working. It can coexist with true hypothyroidism. It cannot be diagnosed with TSH.

***** “Desiccated Thyroid” pills are made from dried porcine or bovine thyroids and contains 30% T3 and 70% T4, both bioidentical with the human hormone (human thyroid tissue contains 20% T3 and 80% T4).

SYMPTOMS OF HYPOTHYROIDISM:

T3 hormone is the efficiency factor for all body parts and the problems resulting from lowered T3 depend on which part of the individual’s body is most sensitive to lack of T3, so symptoms are many and varied.

Note that the TSH test is only relevant to the Pituitary gland’s degree of satisfaction with its T4 supply.

TSH is not related to the body’s degree of satisfaction with intracellular T3, which to date can only be assessed by estimating FT3/rT3.

Many people with Hypothyroidism (either “true” hypothyroidism due to underproduction of T4, or “Functional” hypothyroidism, due to metabolic reduction of thyroid hormone #3 – “T3”, within the cells) report cognitive loss, with sluggishness, anxiety, “brain fog”, and a general feeling of low energy.

As thyroid function deteriorates and slows, so does the rest of the body.

Thus no system is exempt from the effects of Hypothyroidism.

It can make you fat, cause hair loss and dry skin, make your skin coarse and your voice hoarse. It can impact gastrointestinal function, mimicking constipation.

It can affect the eyes, tear glands (“dry eye”), long nerves (peripheral neuropathy), skeletal muscle (weakness and muscle aches) (6) and heart muscle (7, 8) (re muscles, look up Hoffmann’s syndrome and cardiomyopathy).

It can cause leg swelling, puffy eyes and face, numbness and tingling fingers.

In the severest cases, atrial fibrillation, simple heart failure and dilated cardiomyopathy (7, 8).

A SHORT LIST: SYMPTOMS, SIGNS, DIAGNOSIS & TREATMENT OF HYPOTHYROIDISM ***

| SYMPTOMS OF HYPOTHYROIDISM (ABBREVIATED LIST) Fatigue Low motivation Depressed mood Impaired memory Poor sleep quality Weight Gain Depression anxiety Reduced sex drive, male or female Heavy or irregular menstrual “periods” PMS Infertility Recurrent spontaneous abortion Subtle inconsistency of the baby’s brain development Chronic yeast infections Muscle weakness, including Myocardial weakness (see Ref # 6,7,8). Muscle aches Joint Pain, stiffness, swelling Constipation Difficulty staying warm / Increased sensitivity to cold Hoarseness Difficulty breathing Slower heart rate Puffy face Dry skin Acne Brittle hair and nails Thinning hair Calloused heels Headaches Prematurely gray hair | |

| SOCIAL HISTORY OF FUNCTIONAL HYPOTHYROIDISM High-stress job High-stress job partner High-stress life partner Separation, divorce (Parents): difficult children (Children): difficult parents Childhood abuse of whatever origin or type Chronic illness, eg. Celiac Disease or gluten intolerance Severe illness, resulting in continued medical supervision and ongoing anxiety Difficult life circumstances Poverty Dependent relatives Anxious personality disorder or other psychopathy, including schizophrenia and “bipolar disease” Family history of hypothyroidism Retirement, social isolation Alcohol / tobacco / THC /drug dependency | |

| SIGNS OF HYPOTHYROIDISM Slow pulse, Irregular pulse, Low BP, Temperature less than 36°C Dry skin + Dry hair / grey hair Heel calluses Hair loss from the head Hair loss from the legs Hair loss from the eyebrows (outer 1/3) Swelling below lower eyelids Skin swelling over the shins Hoarse, “thick” speech, Dry cough Slow thinking, confusion Memory loss Untidyness Home in endemic area Economic disadvantage FAMILY HISTORY of HYPOTHYROIDISM | |

| TEST RESULTS ASSOCIATED WITH HYPOTHYROIDISM Elevated blood cholesterol level Borderline blood sugar/A1C High TSH, with or without low T4 Low T3, High reverse T3, Low FT3/rT3 ratio, with or without high TSH “Adrenal Fatigue” Low DHEA, Testosterone, Oestrogen, Progesterone, Allopregnanolone Fluid retention, with or without heart failure Iodine &/or Selenium deficiency HEAVY METAL OVERLOAD CAN CAUSE SIMILAR SYMPTOMS: the Urine should be checked for Heavy Metal “burden” | |

| CONDITIONS ASSOCIATED WITH STRESS-RELATED (FUNCTIONAL) HYPOTHYROIDISM POST_COVID SYNDROME, POST_FINASTERIDE SYNDROME, Gulf war syndrome, CFS/FM, CHILDHOOD or ADULT PTSD Goitre, menopause, Psychiatric conditions, autism, Type I or II Diabetes, obesity, peripheral neuropathy, Alzheimer’s, Autoimmune diseases (rheumatoid Arthritis, lupus, sarcoidosis, Sjogren’s, etc.), fibrillation, Dilated, or Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy (See References # 6&7), Crohn’s disease, Ulcerative colitis, Heavy-metal overload, Multiple sclerosis (MS), hypercholesterolaemia, Heart failure, others. Chronic anxiety/depression Schizophrenia ALL TYPES OF SEVERE ILLNESS, or admission to an ICU. | |

| TYPES/CAUSES of HYPOTHYROIDISM 1: Hypothyroidism from iodine deficiency 2: Hypothyroidism from selenium deficiency 3: Hypothyroidism after thyroid inflammation (eg Hashimoto’s thyroiditis) 4: Hypothyroidism from ionising radiation 5: Hypothyroidism from therapeutic radiation 6: Hypothyroidism from surgery, with Thyroidectomy or Hypophysectomy (Pituitary removal) 7: “True” Hypothyroidism of unknown cause 8: Hypothyroidism caused by medication 9: Hypothyroidism caused by stress 10: Worsened Stress Hypothyroidism caused by Eltroxin * 11: Hypopituitarism | |

| TREATMENT Eltroxin*, plus iodine and/or selenium if necessary, for # 1 – 8 Compounded, slow-release T3, for # 9, 10 & 11 Selenium (2 Brazil nuts per day will provide enough). Iodine (2 drops of Lugol’s iodine per day). Iron: your serum iron (“Ferritin”) should be kept >100, if possible. DHEA, 50mg/day (men) and 25-50mg/day (women) reduces symptoms. * Eltroxin makes #9 MUCH worse. |

If you think the above list is fanciful, please read my own history

of FUNCTIONAL HYPOTHYROIDSM,

in the blog post, “ON THE SUBJECT OF FIBROMYALGIA”,

for the whole story.

REFERENCES:

(1) Trans Am Clin Climatol, 2013;124:26-35, Cracking the code for thyroid hormone signaling: Antonio C Bianco 1 PMID: 23874007, PMCID: PMC3715916

(2) Endocrinology, 2021 Aug 1;162(8):bqab059. doi: 10.1210/endocr/bqab059.Deiodinases and the Metabolic Code for Thyroid Hormone Action, Samuel C Russo 1 , Federico Salas-Lucia 1 , Antonio C Bianco 1 PMID: 33720335, PMCID: PMC8237994 (available on 2022-03-15),

DOI: 10.1210/endocr/bqab059

(3) Endocr Rev. 2019 Aug 1; 40(4):1000-1047. doi: 10.1210/er.2018-00275. Paradigms of Dynamic Control of Thyroid Hormone Signaling, Antonio C Bianco 1 , Alexandra Dumitrescu 1 , Balázs Gereben 2 , Miriam O Ribeiro 3 , Tatiana L Fonseca 1 , Gustavo W Fernandes 1 , Barbara M L C Bocco 1 , PMID: 31033998, PMCID: PMC6596318, DOI: 10.1210/er.2018-00275

(4) Clinical Endocrin., Volume81, Issue5, Review, November 2014, Pages 633-641: Defending plasma T3 is a biological priority† Sherine M. Abdalla, Antonio C. Bianco: 05 July 2014 https://doi.org/10.1111/cen.12538

(5) https://hormonetherapyexplained.wordpress.com/2021/10/23/thinking-about-normal/

(6) Hoffman’s syndrome – A rare facet of hypothyroid myopathy, Swayamsidha Mangaraj and Ganeswar Sethy, Neurosci Rural Pract. 2014 Oct-Dec; 5(4): 447–448. doi: 10.4103/0976-3147.140025PMCID: PMC4173264PMID: 25288869 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4173264/

(7) Hypothyroidism-induced reversible dilated cardiomyopathy, by P Rastogi, A Dua, S Attri, and H Sharma, J Postgrad Med. 2018 Jul-Sep; 64(3): 177–179. doi: 10.4103/jpgm.JPGM_154_17

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6066629/

(8) Myocardial Induction of Type 3 Deiodinase in Dilated Cardiomyopathy (experimental, Mice), Ari J. Wassner,1Rebecca H. Jugo,1David M. Dorfman,2Robert F. Padera,2Michelle A. Maynard,1Ann M. Zavacki,3Patrick Y. Jay,4 and Stephen A. Huang1 Thyroid. 2017 May 1; 27(5): 732–737. Published online 2017 May 1. doi: 10.1089/thy.2016.0570PMCID: PMC5421592PMID: 28314380 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5421592/

I can supply further references, on request.